Aircraft Shortage Analysis: Industry Insights and Strategic Recommendations

There’s been a growing gap between air travel demand and the aviation industry’s supply of new aircraft to meet it. While passenger demand has rebounded from pandemic-era lows and is projected to keep growing, delivery times for newly manufactured aircraft—and maintenance turnaround times for aircraft in existing fleets—have slowed.

What are the implications of this aircraft shortage for key stakeholders along the aviation value chain? What future scenarios are possible? What useful steps could industry players take to help level this imbalance and minimize risks?

And, finally, how big is this aircraft shortage, really? Our analysis—using a novel framework and set of data points—indicates that, while significant, it could be less severe than some industry observers might assume.

There’s an ongoing struggle to align passenger demand with aircraft supply

For the past few years, the commercial aviation industry has dealt with uncoordinated swings in travel demand and aircraft supply. Balancing these two variables is a tricky equation.

Passenger demand is highly dynamic and can change quickly. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s been on a rapid rise. Commercial air travel demand, measured in revenue passenger kilometers (RPKs), grew by 10.4 percent from 2023 to 2024 and is projected to grow at an annual rate of 4.2 percent through 2030.

Conversely, the production system for new aircraft can be slow to ramp up due to its complexity. There has been long-standing turbulence in aerospace supply chains, and OEMs have struggled to secure adequate quantities of manufacturing components such as semiconductors and finished castings and forgings. Shortages in both skilled labor and raw materials persist in the wake of the demand whiplash induced by pandemic-era air travel slowdowns. Some aircraft models have been unexpectedly grounded, and some new-engine introductions have encountered early hiccups. These combined challenges, which are unlikely to subside in the near term, have caused delays in both new-aircraft deliveries and maintenance turnaround times.

These delays could potentially be exacerbated by global events. The aviation supply chain—for new and aftermarket needs—is highly international and interconnected. An aircraft’s engine might be produced through a joint venture between companies in two different countries; its avionics might come from a third country; its landing gear might come from a fourth. Ongoing geopolitical tensions and trade concerns could affect critical suppliers, amplifying disruptions.

How severe is the aircraft shortage, really?

There is, without doubt, a current shortage of new aircraft. This is in part due to a monthslong, near-total production halt during the pandemic. Only about 7,000 aircraft were delivered in the six-year period from 2019 through 2024—far below the prepandemic trajectory, which, if it had continued, would have resulted in the delivery of about 12,000 aircraft over that same time frame. By that measure, one might assume a supply shortage of about 5,000 aircraft.

But lost aircraft deliveries don’t, on their own, provide a fully accurate picture of the aircraft shortage in the market. While supply was affected by slowed deliveries, it’s important to remember that the pandemic also interrupted passenger demand, which took years just to recover to 2019 levels.

In our view, a more comprehensive analysis of the current aircraft shortage would also consider delayed aircraft retirements. Slowing the phaseout of aircraft is a primary short-term supply lever for both airlines and aircraft lessors. It’s what they do when they’re concerned about having enough aircraft to meet demand.

The long-term average rate of global aircraft fleet retirements is 2.8 percent annually. From 2019 through 2024, only 1.8 percent of the global fleet was retired annually—nearly 40 percent below the long-term rate. Old aircraft are being kept in service longer because not enough new aircraft are being delivered.

When looking at the aircraft shortage through the lens of this higher-than-expected rate of delayed retirements, our analysis finds that the global shortage could be closer to roughly 2,000 aircraft (with around 75 percent of the shortage relating to narrow-body aircraft). This is considerably smaller than the roughly 5,000-aircraft gap that might be suggested by focusing on the difference between pre- and postpandemic delivery trajectories.

Aircraft shortages affect industry stakeholders in different ways—and not always negatively

Although the current aircraft shortage is likely smaller than some measures might suggest, a shortage of any size can still put pressure on the profitability and growth of various parts of the value chain that are reliant on new-aircraft production. But for stakeholders with ties to existing fleets and aftermarket services, shortages can also create opportunities:

- Airlines can face growth challenges (because they can’t secure enough new aircraft to meet demand) and incur higher maintenance and fuel costs (because the older aircraft being kept in service longer require more upkeep and burn more fuel per seat). But airlines can collectively benefit from increased load factors (meaning more seats are occupied) and higher yields (meaning ticket prices are higher) if capacity is constrained and markets continue to grow—as in the period directly after the pandemic, when demand suddenly outstripped supply and airlines around the world reported record profits. This can play out differently for each airline, depending on its business model, geography, and competitive dynamics, along with its fleet mix, age, and renewal plans.

- Aircraft leasing companies can gain leverage, since they own roughly half of the globally available aircraft in a market with limited supply. Airlines are willing to pay a premium in this context—reflected in rising lease rates, particularly in the narrow-body segment. For instance, the industry intelligence group Aircraft Value Analysis Company reports that the monthly lease rate for a new Boeing 737 MAX 8 rose from a low of $283,000 in April 2021 to $452,000 by April 2025, while the corresponding rate for an Airbus A320neo increased from $289,000 to $442,000 over the same period.

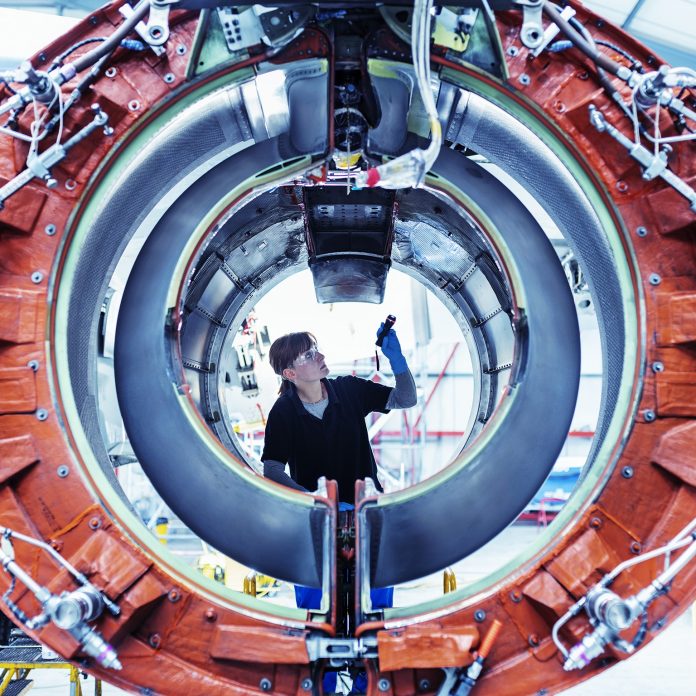

- Maintenance, repair, and overhaul providers (MROs) can thrive in a capacity-constrained market, as extended operation of aging aircraft boosts demand for additional maintenance services such as retrofits, modifications, and installation of margin-accretive spare parts.

- Engine suppliers can benefit from strong demand for both newly manufactured engines and aftermarket services. When aircraft are kept in service longer, they require more engine shop visits—through which suppliers can earn strong margins from selling spare parts. Suppliers can also benefit from nonperformance: Consider that when production rates remained below prepandemic levels in 2024, top engine suppliers’ collective economic performance thrived—earning 18 percent EBITDA margins in 2024 versus 11 percent EBITDA margins from 2017 to 2019.

- Aircraft OEMs and (nonengine) suppliers can struggle due to lower-than-expected new-aircraft production rates. The challenge can be especially acute for suppliers of systems such as aerostructures, which have less aftermarket demand than more maintenance-heavy components.

Could this aircraft shortage transform into a surplus?

We’ve analyzed a multitude of scenarios that could play out along the axes of aircraft supply and travel demand. For instance, demand and supply could deviate further, amplifying the aircraft shortage—and likely helping lessors (as lease rates soar) and MROs (as older aircraft, which require more maintenance, stay in service longer), while offering mixed results for airlines (which could enjoy healthy yields but be limited in their ability to add capacity).

Of all these possibilities, we’ve chosen to focus this article’s analysis on two scenarios that we assess as both plausible and important to contemplate. The first is a soft landing at equilibrium, and the second is a full reversal to oversupply in the next five to ten years. One could require careful collaboration and calibration, and the other could present significant challenges for the industry.

Soft landing at equilibrium

In this scenario, stable growth in air travel demand is met with a steady ramp-up of new-aircraft supply. New-aircraft production would recover to a level that is in line with demand, and retirements of aircraft would rebalance to historically average levels. This is the most favorable scenario for the aviation ecosystem.

The soft-landing scenario could occur in the following circumstances:

- OEMs increase their aircraft production rates in a measured and transparent manner.

- Aviation supply chain performance improves in line with OEMs’ ramp-up and some specific issues are solved (such as lagging performance from components and subtier suppliers, particularly relating to engine parts).

- Air travel demand grows steadily (as per current long-term outlooks) and doesn’t encounter negative shocks relating to, for example, geopolitical tension or economic uncertainty.

- Decelerated fleet renewal at the world’s leading airlines (which could face increased costs and stabilizing yields as capacity development comes in line with travel demand growth) is offset by aircraft demand from fast-growing airlines in developing countries.

A soft landing could be positive for many players in the industry. Aircraft OEMs, engine suppliers, MROs, and airlines could all benefit from equilibrium and stability as OEM production grows in line with demand and the ecosystem is able to plan effectively. Lessors and some niche players—such as late-life-cycle MRO suppliers—could experience recalibration as current, highly favorable conditions settle back to long-term averages.

A reversal straight to oversupply

In this scenario, passenger demand deteriorates at the same time that new-aircraft supply ramps up aggressively. Aviation is a highly cyclical industry, and elements of it can sometimes overcorrect (as has happened in previous downturns). This scenario could create headwinds for many industry players.

The reversal-to-oversupply scenario could occur in the following circumstances:

- OEMs (which have already announced ambitious production growth plans) overcorrect and aggressively increase production in an uncontrolled and uncoordinated manner.

- Air travel demand weakens significantly versus current forecasts—for instance, as a result of a global economic recession—with effects especially concentrated in the highest-yielding flows.

- Airlines’ performance outlook weakens further as a result of rising costs and inflation, while yields dilute as industry capacity grows beyond prepandemic levels (and, in response, airlines decelerate fleet renewal plans).

- In response to ramped-up delivery of new aircraft, a large wave of both overdue and early retirements of existing aircraft hits the market.

A reversal to oversupply could affect various industry stakeholders in the following ways:

- Aircraft OEMs could initially benefit from a large backlog of orders. Eventually, however, overproduction could affect pricing and suppress long-term demand for new aircraft, thus hurting longer-term financials. OEMs could also face downside risks resulting from worsened aftermarket economics.

- Engine suppliers could also benefit from a large increase in orders. However, new engines are often sold at cost or even at a loss. Meanwhile, engine aftermarket services such as maintenance and repair are often a significant component of engine suppliers’ businesses, providing margin-accretive revenue streams. A market oversupplied with many new engines, which tend to need less maintenance and repair, could mean reduced aftermarket business for engine suppliers.

- MROs are likely to suffer as older, maintenance-heavy aircraft are retired. This could be especially hard on MROs that specialize in late-life-cycle services or platforms.

- Airlines could face financial challenges as fewer passengers meet with excess capacity in the market. Overcapacity very frequently leads to fierce competition, lower yields, and higher unit costs for airlines.

- Lessors could be disadvantaged as lease rates fall when aircraft availability becomes plentiful.

Taking steps to encourage equilibrium

To avoid the risks inherent in an oversupply scenario—and to help ensure a balanced outcome for the ecosystem—the industry can consider taking a few proactive, coordinated steps.

Align stakeholders in a controlled production ramp-up

The aviation supply chain is highly interconnected, with only a very small number of producers for many important components. Some players can benefit from a supply–demand gap and thus have little incentive to help right the imbalance (particularly if that would involve deploying capital). Trust among suppliers, OEMs, and airlines—if aligned on a realistic production ramp-up—could be restored through steps such as the following:

- ensuring that senior decision-makers at important suppliers are positioned to manage the scale-up road map, align on production plans, and be the first points of contact who can quickly solve escalations

- creating incentives—using agreed-upon processes and transparent performance management, including dashboards that are accessible to all parties—that will encourage adherence to planning

- establishing engineering and supply chain management centers of excellence to collaboratively assess and close structural capability gaps at suppliers

- carefully weighing trade-offs (such as delaying aircraft production despite large order backlogs) and making decisions by looking through an industry-wide lens that considers knock-on effects

Build more flexibility into delivery contracts

Delivery contracts can have long durations (ten years, in many cases) and little leeway for readjustment. Given the general uncertainty inherent in the aviation industry, crafting delivery contracts that offer more flexibility could help airlines navigate geopolitical and economic challenges—and, in the end, help prevent a buildup of aircraft oversupply in the market.

Rigidly structured delivery slots could also be discarded in favor of more dynamic solutions, which could allow the swapping or trading of delivery slots between airlines and OEMs. OEMs could strengthen customer relationships by helping their customers identify beneficial opportunities to trade delivery slots with other airlines or even with other OEMs.

Undertake capital expansions thoughtfully—with copious scenario planning

Any aviation industry player contemplating expansion plans should construct them in ways that allow flexible adaptation to varying market conditions. Modeling best-, base-, and worst-case traffic and production forecasts (that account for variables such as macroeconomic changes, fuel price hikes, and geopolitical risks) can help identify different fleet needs under each scenario. Models should include scenarios in which older aircraft are retired early or leased jets are returned, allowing flexibility in the event that demand undershoots expectations.

FAQs

What are the main factors contributing to the aircraft shortage?

The main factors contributing to the aircraft shortage include slow ramp-up of new aircraft production, disruptions in the aerospace supply chain, delayed retirements of existing aircraft, and geopolitical tensions affecting critical suppliers.

What are the potential scenarios for the future of the aviation industry in terms of aircraft supply and demand?

Potential scenarios include a soft landing at equilibrium, where supply and demand are balanced, and a full reversal to oversupply, where passenger demand weakens while new-aircraft supply ramps up aggressively.

Conclusion

A soft landing that balances supply and demand could offer favorable outcomes across the entire aviation industry. Through careful analysis and collaboration, stakeholders can help navigate the industry toward a healthy equilibrium.